RESEARCH

Support for this project included a grant from the TAFP Foundation.

Clinician and patient experiences with medical interpreter use in a family health center

AUTHORS

Tharani Ravi, MD; Jasmine Rodriguez, MPH; Robert Wood, DrPH; Anthony Pascullo, MS; Etny Candelario, MD; Daniela Estrada, MD; Mario Hernandez, MD; Carolina Sanchez, MD; and Fozia Ali, MD

Author information

Tharani Ravi, MD

UT Health San Antonio

Jasmine Rodriguez, MPH

UT Health San Antonio

Robert Wood, DrPH

UT Health San Antonio

Anthony Pascullo, MS

UT Health Long School of Medicine

Etny Candelario, MD

UT Health San Antonio

Conviva Care Centers

San Antonio, Texas

Daniela Estrada, MD

UT Health San Antonio

Mario Hernandez, MD

UT Health San Antonio

Chen Senior Medical Center

Miami, Florida

Carolina Sanchez, MD

UT Health San Antonio

Fozia Ali, MD

UT Health San Antonio

The United States is a melting pot of ethnic and linguistic diversity. Effective communication and understanding of cultural contexts are paramount in delivering quality care to patients from different ethnic and linguistic backgrounds. [1] Research shows that language barriers contribute to poor treatment adherence, decreased patient comprehension of their diagnoses, and increased associated complications. [1] Professional interpreters are associated with improved clinical outcomes, increased patient satisfaction, and decreased communication errors. [1, 7, 8]

Exploring the hurdles encountered by clinicians when using medical interpreters is crucial because of their potential adverse effects on patient communication and clinician satisfaction. A national survey from 2006 revealed that 58% of resident physicians faced significant challenges in delivering care due to time constraints, while 54% encountered difficulties due to limited access to interpreters. [9] Due to time limitations, poor interpreter access, and technical problems with interpreter access devices, residents and physicians in practice often chose to underutilize interpreters or used ad hoc interpreters instead. [10 – 12]

Our Family Health Center (FHC) is a family medicine residency-based clinic, set in an urban, low-income area of Bexar County, Texas, where roughly 13% of the population is foreign-born, with Hispanics/Latinos comprising 60.3%. [2] Additionally, 48% of the population speak a language other than English at home. [2] Notably, since 2021, the clinic has also been serving Afghan refugees. Qualified phone/video interpreter services are available; however, clinicians reported concerns about limited English-proficient (LEP) patients not comprehending their health care plan despite using medical interpreters.

This study aimed to gain a deeper insight into clinician satisfaction and comfort with medical interpreter use, gather clinicians’ perceptions of how interpretation influences the quality of medical care provided, and to identify barriers to effective communication when using medical interpreters. The study also explored patient experiences when using interpreters and contrasted them with clinician experiences.

Methods

In 2021, we conducted a mixed methods study consisting of surveys and focus groups. Two provider surveys: "Clinician Survey” and “Staff Survey” were collected. “Clinician Survey” was completed by the clinic’s family medicine faculty, resident physicians, and pharmacologists. “Staff Survey” was completed by medical assistants (MA) and licensed vocational nurses (LVN). Surveys were designed based on review of medical literature and FHC providers’ experiences using medical interpreters. Surveys assessed clinician and staff satisfaction with the care provided using medical interpreters, comfort level with interpreter use, and barriers that prevented use of medical interpreters when needed. Patient surveys were collected from Spanish-speaking patients; these surveys asked patients how well their concerns were addressed by their providers and how well they understood their provider’s instructions and advice when using qualified interpreters.

Additionally, we conducted two focus groups using a semi-structured format — one for residents and another for faculty physicians — to delve into barriers to effective interpreter use. The sessions were recorded and anonymously transcribed. Two project team members independently analyzed transcriptions and met to discuss agreement of coding and themes. The thematic analysis was conducted utilizing ATLAS.ti software.

The project was approved by both the UT Health San Antonio IRB and University Health System IRB.

Results

Provider surveys

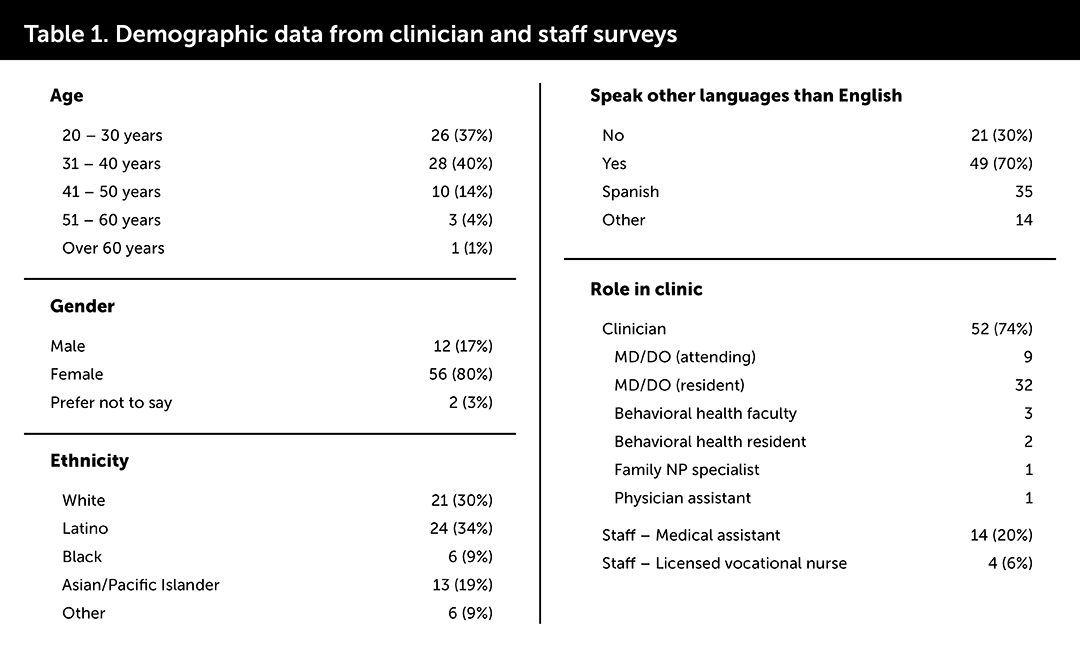

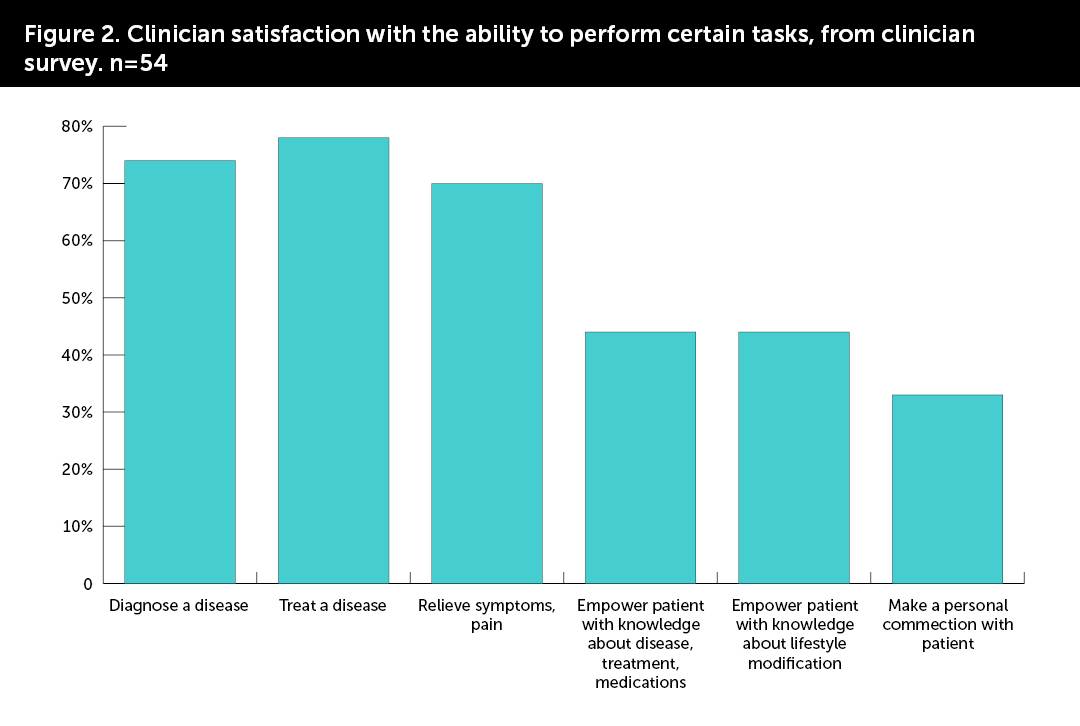

Of the 70 clinicians and staff who participated in the surveys, 52 (74%) were clinicians,14 (20%) were MAs, and 4 (6%) were LVNs. Twenty-four (34%) reported using medical interpreters for one to five clinic encounters in the preceding three months, and 20 (29%) for more than 10 encounters. See Table 1 for additional demographic information.

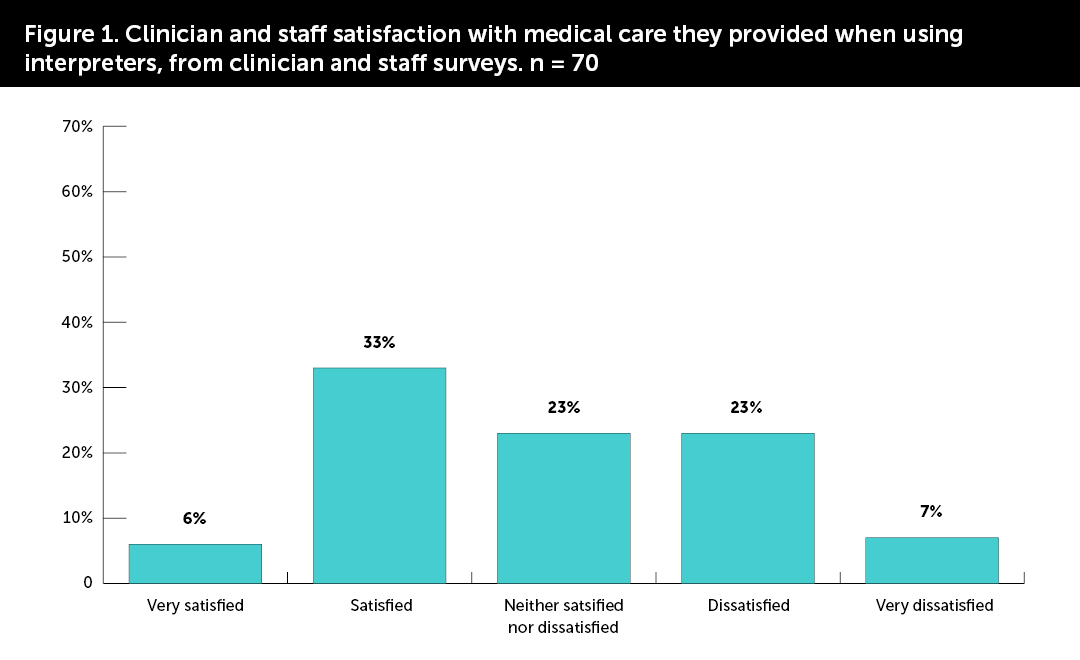

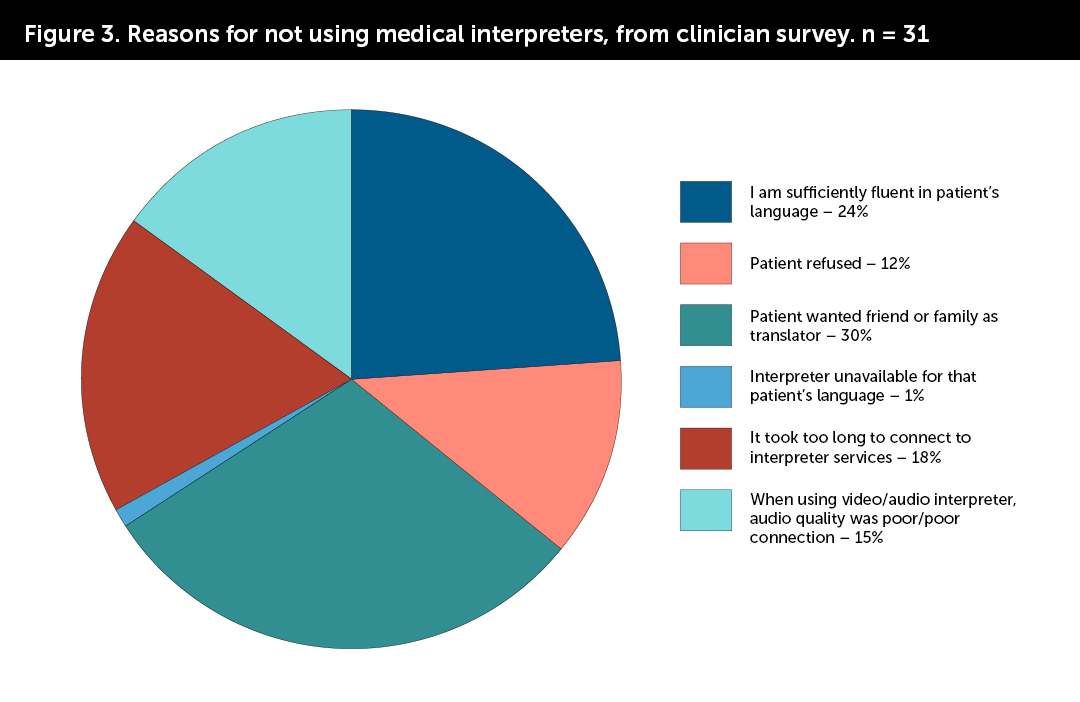

Eighty-seven percent of clinicians and staff were at least “somewhat comfortable” using medical interpreters and 76% felt they were able to overcome language barriers through interpreter use. However, only 39% were satisfied with overall medical care provided during visits when they used medical interpreters. (Figure 1) Most clinicians (70%) stated they were satisfied with their ability to diagnose and treat a disease when using interpreters; but fewer than half were satisfied with their ability to empower patients (44%) and make personal connections (33%). (Figure 2) Fifty-one percent of clinicians did not use a medical interpreter at least once in the past three months in a clinic encounter with a LEP patient due to various barriers; including high wait times to connect to interpreters, poor quality of interpreter phone connection, and patients’ preference to use family/friend as interpreter. (Figure 3)

Provider focus groups

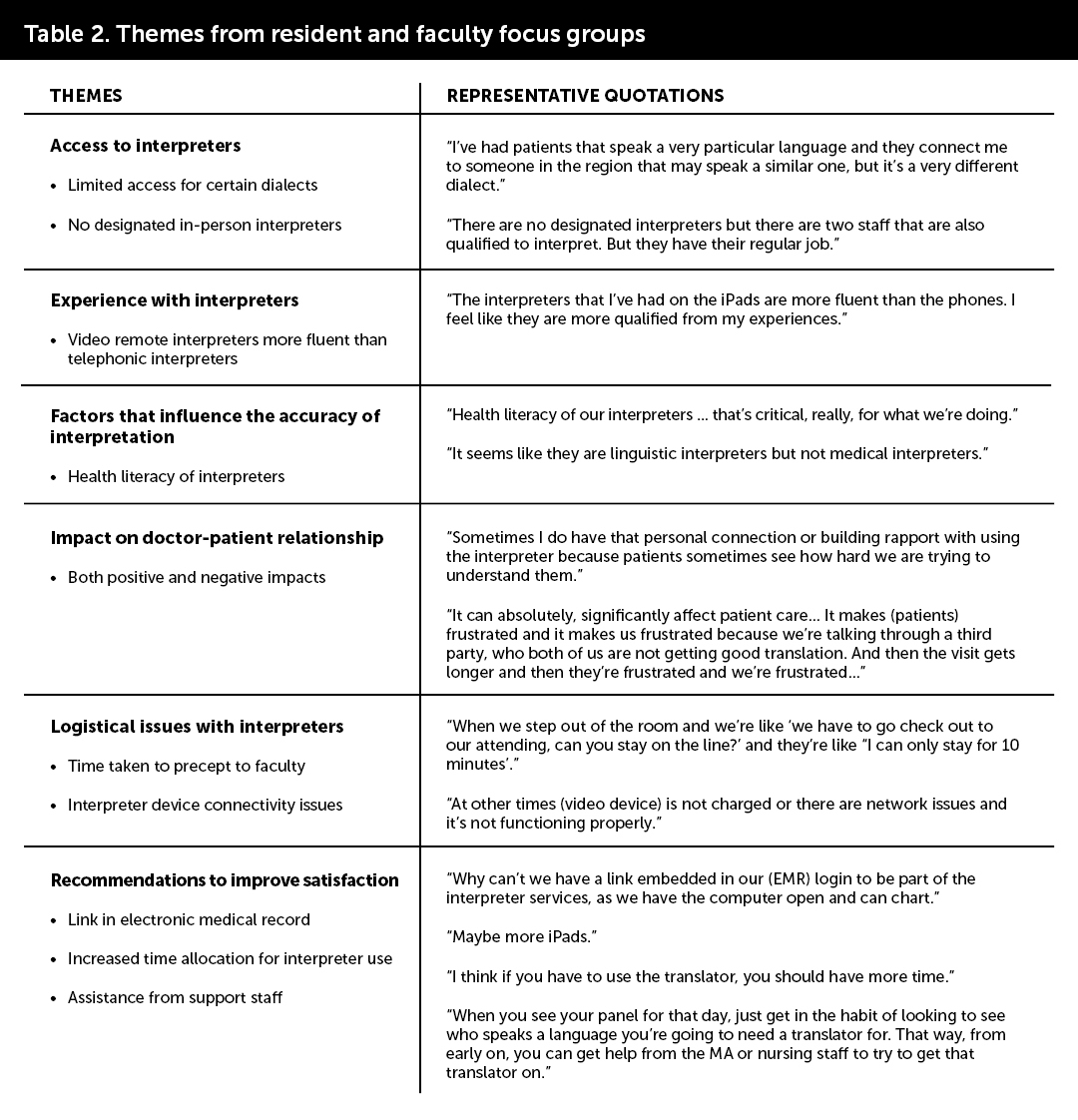

Eight family medicine resident physicians participated in the resident focus group and eight family medicine faculty participated in the faculty focus group. The focus group discussions unveiled several critical themes on provider experiences when using medical interpreters at the Family Health Center (FHC) clinic.

Access to interpreters emerged as a significant challenge experienced by the participants, with limited availability for specific dialects. Participants also expressed challenges in requesting an interpreter of a specific gender, which were frequently requested by Afghan patients. In addition, they highlighted the absence of designated in-person interpreters, and the availability of only two video interpreter devices.

Factors influencing the accuracy of interpretation were discussed. Participants noted substantial variability in interpretation accuracy and health literacy of interpreters. "It seems like they are linguistic interpreters but not medical interpreters," stated a participant.

Logistical and technical issues with medical interpreter services were another prominent concern. One example noted by resident physicians was speaking through a third party and shuttling between patient rooms to precept with attending physicians. Additionally, both attendings and resident participants reported long wait times, poor connectivity and low-quality audio. They also highlighted challenges where interpreters were unable to stay on the line for the required duration or technical issues with the devices, affecting the smooth flow of communication during appointments.

Participants also noted differences in proficiency between video remote and telephonic interpreters. They perceived the interpreters using video devices to be more fluent and qualified.

Participants explored the impact of medical interpreter use on the physician-patient relationship, noting both positive and negative effects. Many felt that the logistical barriers and inconsistent accuracy of interpretation negatively impacted their capacity to establish positive patient-physician relationships. Conversely, others believed that patients valued physicians’ attempts to comprehend them, despite the additional time and effort required for interpreter use. Some physicians felt their relationships with certain LEP patients were stronger than those formed during language-concordant visits.

Recommendations to improve satisfaction with interpreter services included integrating a link within the electronic medical record (EMR) for seamless access, allocating increased time for interpreter use during appointments, seeking support from additional staff members to facilitate interpreter coordination, and obtaining more video devices.

Patient surveys

Seventy-two patient surveys were collected from Spanish-speaking patients. These were all patients established in our clinic for more than two years. Ninety-four percent of patients responded they understood their doctor’s advice very well or extremely well when using qualified interpreters. Eighty-seven percent felt that their symptoms and concerns related to their health were adequately addressed when their doctor used a qualified interpreter. When asked about the types of interpreters used in clinic in the past year, 26% of patients reported that they used an in-person qualified interpreter, 68% used an interpreter through a video device, 57% used an interpreter via telephone, and 11% used a family member. Except for two patients, the patients’ comments on their experiences with qualified interpreters were very positive, they felt that the interpreters were very professional and had a good vocabulary. Two patients felt that the interpreter sometimes did not translate everything they said and one of them preferred an in-person interpreter.

Discussion

Overall, FHC clinicians and medical staff reported comfort with accessing interpreter services and, through the use of medical interpreters, most clinicians were able to perform their essential duties. However, clinicians were not satisfied with the medical care provided and relationships established with patients. In contrast to provider experiences of dissatisfaction with the care they provided when using qualified interpreters, patient surveys indicated that patients generally were able to communicate well with their providers and get their concerns adequately addressed through the use of qualified interpreters; the patients really appreciated the interpretation services.

Provider focus groups and surveys helped identify specific challenges with the logistics of interpretation, including technical issues related to interpreter devices, interpretation accuracy, and time pressures. (Table 2) They also underscored the need for more video interpreter devices, which were perceived as supporting better quality interpretation than audio-only devices. It is also important to highlight that a significant number of clinicians (30%) cited patient request for using a family member/friend as an ad hoc interpreter as the reason for not using a trained interpreter. Eleven percent of patients also stated they used a family member/friend as an interpreter in the previous year. It would be interesting to delve into the degree to which time delays connecting to interpreters, poor audio quality, and inaccuracy of interpretation influenced these patients’ decisions.

Through the funding provided by the Texas Academy of Family Physicians Foundation, our clinic has been able to understand the challenges our clinicians and patients face when using interpreters. The findings of this study prompted the clinic to develop a quality improvement initiative in collaboration with the health care institution’s Interpreter Services department, to address the challenges faced by clinicians when using medical interpreters. This study can help other programs monitor for similar issues during language discordant visits so they can develop strategies to improve experiences during these encounters, and mitigate the barriers to effective communication.

TAFP Foundation Family Medicine Research Endowment Program

The Family Medicine Research Endowment Program provides a stable source of income to fund practice-based research in Texas. You can create a research fund in your name or the name of a colleague you wish to honor. All of the funds will be part of the Family Medicine Research Endowment Program. Collectively the funds will support the research efforts of the TAFP Foundation. Each fund honoree will be identified as a Family Medicine Research Champion.

Thank you to our current Family Medicine Research Champions and to all those who have donated to an endowment.

Gold Level

Richard Garrison, MD; David A. Katerndahl, MD; Jim and Karen White

Silver Level

Carol and Dale Moquist, MD

Bronze Level

Joane Baumer, MD; Gary Mennie, MD; Linda Siy, MD; Lloyd Van Winkle, MD; and George Zenner, MD

- Karliner LS, Jacobs EA, Chen AH, Mutha S. Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health Serv Res. 2007; 42:727–54.

- Data USA: Bexar County, TX. https://datausa.io/profile/geo/bexar-county-tx/#demographics Accessed September 17, 2020

- Freeman GK, Rai H, Walker JJ, Howie JG, Heaney DJ, and Maxwell M. Non-English Speakers Consulting with the GP in Their Own Language: A Cross-Sectional Survey. British Journal of General Practice. 2002; 52:36–38.

- González HM, Vega WA, Tarraf W. Health care quality perceptions among foreign-born Latinos and the importance of speaking the same language. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010 Nov-Dec;23(6):745-52.

- Manson A. Language concordance as a determinant of patient compliance and emergency room use in patients with asthma. Med Care. 1988; 26:1119–28.

- Perez-Stable, EJ, Napoles-Springer A, Miramontes JM. The Effects of Ethnicity and Language on Medical Outcomes of Patients with Hypertension or Diabetes. Medical Care. 1997; 35:1212–9.

- Flores G. The impact of medical interpreter services on the quality of health care: a systematic review. Med Care Res Rev. 2005 Jun; 62(3):255-99.

- Jacobs B, Ryan AM, Henrichs KS et al. Medical Interpreters in Outpatient Practice. Annals of Fam Med. 2018;16:70-76

- Lee KC, Winickoff JP, Kim MK, Campbell EG, Betancourt JR, Park ER, Maina AW, Weissman JS. Resident physicians' use of professional and nonprofessional interpreters: a national survey. JAMA. 2006 Sep 6;296(9):1050-3

- Diamond LC, Schenker Y, Curry L, Bradley EH, Fernandez A. Getting by: underuse of interpreters by resident physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(2):256-262.

- Sandler R, Myers L, Springgate B. Resident physicians' opinions and behaviors regarding the use of interpreters in New Orleans. South Med J. 2014 Nov;107(11):698-702

- Mayo R, Parker VG, Sherrill WW, Coltman K, Hudson MF, Nichols CM, Yates AM, Pribonic AP. Cutting Corners: Provider Perceptions of Interpretation Services and Factors Related to Use of an Ad Hoc Interpreter. Hisp Health Care Int. 2016 Jun;14(2):73-80

- Rosenberg E, Leanza Y, Seller R. Doctor-patient communication in primary care with an interpreter: physician perceptions of professional and family interpreters. Patient Educ Couns. 2007 Aug;67(3):286-92.

- Kim SC, Kim S, Boren D. The quality of therapeutic alliance between patient and provider predicts general satisfaction. Mil Med. 2008 Jan;173(1):85-90.

- Locatis, C., Williamson, D., Gould-Kabler, C. et al. Comparing In-Person, Video, and Telephonic Medical Interpretation. J Gen Intern Med. 2010 25, 345-350

- Fiedler J, Pruskil S, Wiessner C, Zimmermann T, Scherer M. Remote interpreting in primary care settings: a feasibility trial in Germany. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022 Jan 24;22(1):99.

- Friedberg MW, Chen PG, Van Busum KR, Aunon F, Pham C, Caloyeras J, Mattke S, Pitchforth E, Quigley DD, Brook RH, Crosson FJ, Tutty M. Factors Affecting Physician Professional Satisfaction and Their Implications for Patient Care, Health Systems, and Health Policy. Rand Health Q. 2014 Dec 1;3(4):1.

- Williams ES, Konrad TR, Linzer M, McMurray J, Pathman DE, Gerrity M, Schwartz MD, Scheckler WE, Van Kirk J, Rhodes E, Douglas J. Refining the measurement of physician job satisfaction: results from the Physician Worklife Survey. SGIM Career Satisfaction Study Group. Society of General Internal Medicine. Med Care. 1999 Nov;37(11):1140-54.

- Haas JS, Cook EF, Puopolo AL, Burstin HR, Cleary PD, Brennan TA. Is the professional satisfaction of general internists associated with patient satisfaction? J Gen Intern Med. 2000 Feb;15(2):122-8.

- Bagchi AD, Dale S. Examining Effectiveness of Medical Interpreters in Emergency Departments for Spanish-Speaking Patients With Limited English Proficiency: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2011 Mar;57(3):248-256

- Ferguson WJ. Culture, language, and the doctor-patient relationship. Fam Med. 2002 May;34(5):353-61.